Psycho-Pass: A Tale of Twos

Two seasons, two villains, two different sets of questions

Psycho-Pass is 2012’s thrilling cyberpunk crime thriller anime, and has been one of the most interesting modern (if just shy of a decade old still counts as “modern”) entries into the cyberpunk genre space since its release. Set in the year 2112, in a technologically advanced Japan, the story’s two seasons revolve around two competing, yet intertwined axes: the human experiences of our core cast; and the cold, calculating Sibyl System that controls and organizes society. This story asks questions of both the viewer and the characters — and demands answers. What I want to do here is compare and contrast the core conflicts and questions of the two seasons of Psycho-Pass, and consider how the show answers those questions — both rhetorically and narratively.

But before we go too far, let’s set the stage for the uninitiated.

In the show, the Sibyl System is a technological marvel that interprets personality traits and behaviors to generate extensive profiles, which it uses to determine the best occupation for each citizen, manage their place in society, and record their crime coefficient — their calculated risk of committing crime and harming others. It also uses cymatic scans (brain scans) to judge the mental and emotional state of each citizen, using that data to determine the titular Psycho-Pass of each person. This system is omnipresent in this society — unavoidable and ever-watchful.

This combination of Bentham’s Panopticon and a gentler application of social and hierarchal determinism seen in Huxley’s Brave New World has led to, on the face of things, a utopian society that has successfully minimized conflict, stress (through management and new medication), and crime.

Mostly.

Our protagonist, Akane Tsunemori, is a fresh faced Inspector at the Ministry of Welfare’s Public Safety Bureau (the Psycho-Pass equivalent of the FBI) tasked with solving crimes with the aid of Enforcers, latent criminals (individuals with a naturally high crime coefficient) that opted to help solve crimes instead of being locked in a facility for “the good of society”. Her job is to solve the crimes that Sibyl doesn’t outright prevent with the help of the Dominators — Sibyl-assisted hand cannons that automatically determine the lethality or non-lethality of a shot determined by the target’s crime coefficient. With the context I’ve provided, and the genre of the work itself, the grisly nature of these cases should be obvious. It’s a good thing Akane’s Psycho-Pass is incredibly stable and clear — she’s got a good head on her shoulders. Working with her fellow Inspectors and Enforcers, she works to keep the perfect society Sibyl has facilitated intact and stable.

Everything I’ve described thus far should have elicited some questions. How does Sibyl work? How to people react to the system? If the system is perfect, why is there still crime at all? So on and so forth. These surface level questions, and the meatier ones beneath them, are the core focus of this article — but every question needs a curiosity to exist. A vehicle for the conflict between what the understood and the as-of-now arcane.

The villains of Psycho-Pass are, as with most fiction, perfectly suited for the job. Almost as if they were created for that purpose specifically. Funny how that works.

I’ve broken down a selection Psycho-Pass’s villains, their questions, and the conflicts they challenge the protagonists with, into series of pairs, with each discrete pair building upon the core duality of the show itself. Let’s start with season one.

Season One: Shogo Makishima and the Ring of Gyges

“To live is not merely to breathe; it is to act”

- Rousseau

In Plato’s Republic, a tale is told of a man who discovers a magical ring that can turn him invisible. He then uses the power of this ring to infiltrate his local king’s court, seduce the queen, and seize power. This is the Ring of Gyges, and in Republic Glaucon asks whether it is possible to be virtuous if you have the power to commit any injustice with no accountability or retribution.

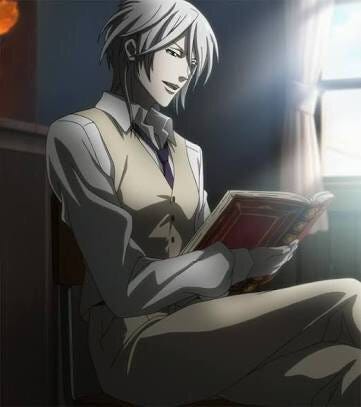

In the context of Psycho-Pass, the main villain of season one is a living, breathing, philosophizing Ring of Gyges. Shogo Makishima is an anomaly in the Sibyl System; he has a crime coefficient too low for any alert or enforcement by the Dominators. His Psycho-Pass is the as clean and perfectly white as his hair. When he kills, his crime coefficient only decreases. He can operate entirely without fear of retribution. So he does, using his genius-level intellect to leave (directly or indirectly) a trail of bodies and blood behind him that no other single actor has been able to match in the show’s internal history.

On the surface, the show presents the answer to Glaucon’s question quite clearly: “No”. But it’s not so simple. In a twisted way, Makishima is acting out of humanist virtue — he believes that the Sibyl System has tainted and buried the ideas of human expression, free will, agency, and authenticity. Indeed, we see direct evidence of this in the show; there are people who have undergone so much stress therapy to keep their Psycho-Pass clear that they’ve become nearly living zombies. They’re technically awake, but there’s no life in them anymore.

Makishima hates that. He sees the potential of humanity and wants to eviscerate that which is suppressing it: the Sibyl System. So while the steps he takes towards his goal are violent, reprehensible, and bloody, his end goal is almost laudable. In a perverted sense, he’s a lone deviant fighting for idealized freedom in the most perfect surveillance state ever constructed. So the question now becomes twofold: Is he actually a virtuous man, using the Ring of Gyges for good? Do the ends justify the means? The latter answer is almost certainly “no” — I don’t think that ruthless calculus is possible for a human. But the former? I’m not so sure.

Throughout season one, Makishima enables and encourages a collection of serial killers who have managed to lay low or avoid detection by Sibyl. Every one of these relationships is a combination of curiosity and examination from him, to determine who was the most willing to embrace their true selves despite the risk, and to “see the color of their souls”. Every partner or student represents a threat to the system, a flaw, a failure, and so he cultivates them until they lose their way or become a liability. Everything he does, even casually, is tinged by his crusade.

Earlier I mentioned how I was going to discuss things in terms of pairs, and until now I’ve only discussed a single individual. While Sibyl is a valid counterpart (and the logical starting point), I intend to save that for later. The value (and therefore the difficulty) with Makishima is that he reaches out and touches the core protagonist cast in a variety of unique ways, but there are two pairings that stand out: His push and pull with Akane, and his push and pull with her closest Enforcer Shinya Kogami, an ex-Inspector that became a latent criminal investigating Makishima in the past.

The latter relationship is one that the show spends a lot of time on, highlighting the similarities between Makishima and Kogami in style, intellect, capability, and ideals, and the slowly-closing gap between the two. It’s also the relationship that’s been analyzed to death online, so I’m not going to discuss that. Instead, I’m going to discuss the relationship between Akane Tsunemori and Shogo Makishima — a deviant, twisted crusader against the system and status quo, and an honest, genuine, morally upright defender of the public.

As Akane learns and experiences more in her role as Inspector, she begins to see the cracks in the Sibyl System and question it. She starts the show naïve, but doesn’t stay that way for very long. She acts on her own judgement, trying to minimize death whenever possible to maximize the chances of a culprit rehabilitating and rejoining society — even when Sibyl tells her Dominator to use lethal force. She pushes back on the system from the inside, bending the rules just enough for her moral foundations to come out on top.

In this, Akane is a foil of Makishima. While not as perfect or asymptomatic, Akane’s Psycho-Pass is clear enough to let her track Makishima and grow to match him almost as well as Kogami. She also sees the flaws in the Sibyl System (especially near the end of season one, where she learns the secrets of the system itself), and understands Makishima’s conclusions. But there are two crucial differences between the two: Akane sees the good that Sibyl has brought to people, and she thinks she can improve and change things from the inside.

This relationship is, at its core, a tug-of-war between a moral reformist and an “at any cost” revolutionary. Between someone fulfilling her duty to the people, if not the law, and a twisted messiah bent on breaking the pleasant utopian chains of this world. The word “messiah” being deliberate, with Makishima quoting the Parable of the Weeds (Matthew 13: 24–30) in a moment of self-indulgency at the culmination of his plans. The contrast between Akane and Makishima is one of tactics, morality, and purpose, and that’s what makes this comparison interesting. Where Makishima sees people only as faces or aspects of a larger abstract intellectual “humanity”, Akane cares about each person individually, empathetically connecting with them as she tries to save them. Where one feels isolated by the system and wants to destroy it, the other sees its value and wants to reform it. Where Makishima sees chains, Akane sees structure — and they’re both right. That is why this particular connection is compelling; Akane stands as the moral opposite to Makishima at every step, and she is the viewer’s stand-in for the questions posed in the narrative.

Using this strategy in the first season of the show is a beautiful narrative decision, as it allows the show to directly ask and answer the questions that learning about the setting would evoke. The setting, characters, and plot all come together around these questions to guide you along an exemplary narrative experience.

So what do you think? Do the ends justify the means? Can such a system as Sibyl exist and be just? To link back to the start of this section, I have two questions. If you had such a Ring of Gyges, what would you do? And, to foreshadow both the end of season one and the end of the article, I ask: What if you weren’t the only one?

Season 2: Kamui and Togane — Jury and Inquisitor

“Justice must always question itself, just as society can exist only by means of the work it does on itself and on its institutions.”

― Foucault

Season 2 of Psycho-Pass is widely considered to be a step down from its predecessor. There are several reasons for this; the characters felt less integral to the philosophical questions, the villains weren’t as charismatic, the runtime was noticeably shorter, and so on. I say this to explain why this section is going to be significantly shorter than the previous one — there isn’t as much depth, even if the questions are still interesting.

The pairing I’ll be discussing today is not between the protagonists and antagonists, but between the two different villains of season two: Sakuya Togane and Kirito Kamui. Much like our previous pair, these two represent a defender of the Sibyl System and a crusader against it — but things are different this time.

Kamui is the sole survivor of a plane crash caused by corporate greed and failure, and has the remains of the other 150 or so survivors surgically implanted in him afterwards (including brain parts). As he healed, he found himself disappearing from the Sibyl System entirely — he was entirely invisible to the cymatic scans and therefore also had no crime coefficient. Again, he’s gifted an even more effective Ring of Gyges, and again he stands in conflict with Sibyl.

However, the difference is that where Makishima wants the immediate destruction of the system, Kamui questions it and demands an answer. As a walking collective invisible to individual judgement, he demands to know how Sibyl can be perfect when it can’t judge groups for their sins (because the individuals may not be subject to enforcement). He also presents the main question of the season: what color is the Sibyl System? What is the Psycho-Pass and crime coefficient of the system that judges and monitors everyone else? Kamui is making an (again abstract) moral stance against the Sibyl System by arguing as a population unto himself, seeking to be a stand-in jury to judge the Sibyl System itself. If the System has the right to judge, so does he.

While these questions are relevant and interesting, they’re repeated in the narrative explicitly and are not engaged with on a deeper level, making it feel more like the show is paying lip service to the ideas rather than truly engaging with them. To avoid spoilers, I’ll merely say that the question is built on a variation of the Omnipotence Paradox, and explores the relationship between Sibyl’s ability to judge itself and it’s “perfection”. Another narrative flaw here is that Kamui falls into the trap of “the last villain’s gimmick, but more”; where Makishima was asymptomatic within the system, Kamui simply doesn’t exist. Kamui is less sadistic, but he also commits crimes (murder, manipulated police brutality, terrorism, brainwashing) to achieve his goal much like Makishima, if with a veneer of regret and sadness. Like Makishima, Sibyl takes an interest in him, and he presents a series of unique tests to Akane.

He’s just less interesting, and doesn’t dig his roots deep enough into the context and themes to be as compelling.

Something similar can be said for Sakuya Togane, the dark inquisitor of the Sibyl System. Togane is a new Enforcer put under Akane’s command, and has the highest crime coefficient on record (just shy of 900 — lethal force is authorized at 300). His Psycho-Pass is pitch black. As the secondary antagonist of the show, he had the potential to be both immensely compelling and far more effective — but the show’s runtime did not allow him the time to become so. For reasons I’d have to spoil the show to give, he emphatically tests and corrupts Inspectors to keep Sibyl as pure and perfect by comparison. His goal in season 2 is to paint Akane’s Psycho-Pass black, to entirely corrupt her. He works within the bounds of the Sibyl System, reads up on Akane, starts mirroring scenes and behaviors from Kogami in season one (who isn’t in the picture for most of season 2), and more all to get close to her for this purpose. Where Kamui is a collective aiming to judge something higher than themselves, Togane is a single, selfish, sadistic soul that takes pleasure in breaking the very people working for the system — with the system’s tacit approval.

This kind of malicious manipulator, intent not on murder but on complete corruption and control, serves as a vehicle not for his own unique question, but as another piece of evidence pointing to the imperfections in Sibyl’s judgement and structure. Instead of the show leading us toward multiple possible answers and interpretations of the given questions (like in season one), season two repeatedly points back to the same core conceit like a high school English student pointing out color symbolism in The Life of Pi. Interesting, but not the most complex or compelling. The problem with Togane is multifaceted: he’s not given enough episodes to really develop his plan and push that creeping unease and tension on the audience, and his character is entertaining, but ultimately philosophically static within the text. Which is disappointing, as he’s quite fun to watch on-screen.

While I do recommend watching both seasons of the show (and the movie), I want to make it extremely clear that expectations for season two should be lower than season one. However, the final, core pairing I named at the start of the article is best discussed with context from both seasons.

The Sibyl System vs. Humanity — What Is It Worth?

“Surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action.”

― Foucault

Is the relatively peaceful utopia that the Sibyl System does produce worth the cost in freedom, expression, and self-determination? That’s the core question of the show, the common through line in the text that every character works around, that every villain rails against, and that the audience is intended to engage with.

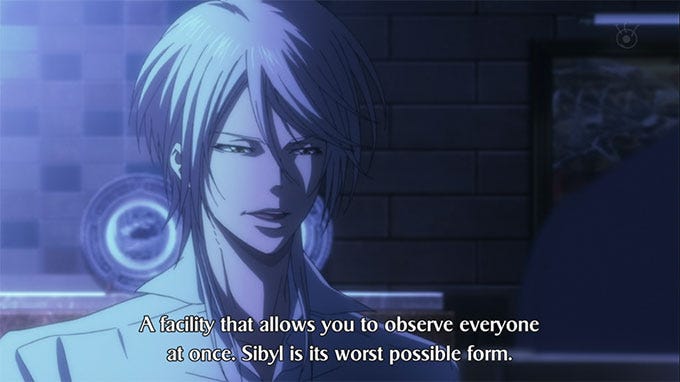

The Sibyl System represents both an evolution for humanity, and an entity that has completely cut itself outside of that process. It was a human invention designed to perfect criminal justice and social organization via near-perfect surveillance and computational analysis. However, it also represents an un-judgable, abstract, undemocratic entity that has the power to permanently change the lives of each and every citizen. In the show we see people dissatisfied with their chosen career path growing despondent or mentally ill from the tedium and frustration. Even when Sibyl is not actively watching certain individuals — where the Eye of Sauron is pointed elsewhere — every single person in the setting of Psycho-Pass must act and live as if they’re being intently watched. Makishima explicitly names Sibyl as the technological Panopticon in season one, and it’s the perfect comparison: the citizens are the prisoners, looked down on by a single towering entity above them but unable to look back up and see it themselves.

Makishima sees this as a limit on freedom, on human nature, on free will, and on what it means to be “alive”. To him, it is a sin in both ideal and outcome. Akane sees the peaceful and mostly-happy society built under Sibyl, and wants to protect the people in that society. To her, it’s an unpleasant necessity for a net-positive outcome. Kamui views it as a contradiction and a hypocritical entity. Togane views it as a perfected being to be idolized. While the levels of fervency in their beliefs vary from character to character, every one of them has a distinct perception of the Sibyl System that informs their actions. However, only the former two have solutions: revolution and reform. Bring down the system and encourage growth from the ashes, or improve and refine the system from within to minimize harm.

So, my question to you is this: is the outcome of the Sibyl System worth it to you, even with its imperfections?

If not, what is your solution? What would you change? Would you destroy it entirely, or merely adapt? What would you do about the society of people used to safety and surveillance suddenly losing both?

I’d love to hear your responses below. Thank you for making it to the end of this long essay; I hope you enjoyed reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it. I’ve kept the major spoilers and plot beats to a minimum, so please go watch the show yourself! I highly recommend it.